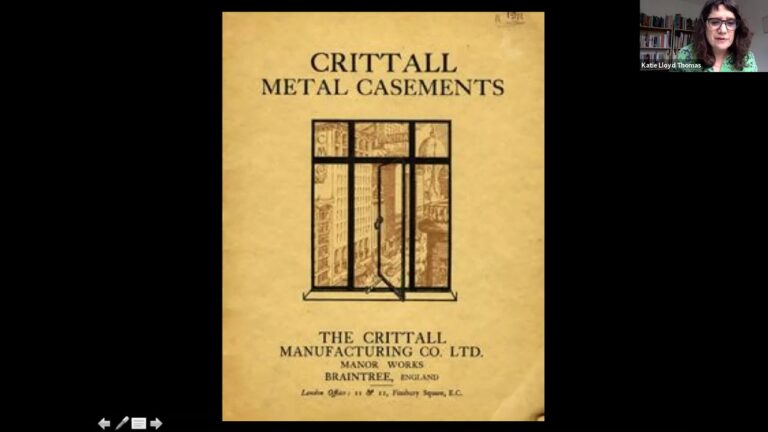

In this paper I look at the emergence of the proprietary specification as a key aspect of the architect’s practice in the interwar period in the UK. For the first time, at least at scale, the architect took responsibility for selecting one branded building product over another – Venesta Ltd over Flexo Plywood Industries; Critall’s windows over Henry Hope and Sons Ltd; Ripolin paint over Pinchin Johnson and Associates. If manufacturers could persuade the architect to enter their brand into the legally binding document sales were guaranteed.

This change not only put architects into a new position – becoming product brokers on behalf of industry – it also extended the kinds of jobs available in the building industry from traditional work on the construction site to the factory and sales floor, and helped open the industry to women as well as men. Their involvement, as building products saleswomen, as electrical demonstrators and as factory workers led, I argue, to a ‘feminisation’ of a hitherto technical arena, but also raises the question of the changing sites of building labour. If as Sérgio Ferro has argued, ‘the building site occupies a special position in the sphere of social production’ because it remains a manufacture ‘fundamentally characterised by the essential operational role of labour power’, why during this period did it do more than ’only occasionally resort to industrial products (materials, components, some non-essential machines)’ and with what effects?[1]

Katie Lloyd Thomas is Professor of Architectural Theory and History at Newcastle University and an editor of Architectural Research Quarterly. Her research focuses on materiality, technology and the production of architecture. She will present her research on the architect’s role in the circulation of proprietary building products in the interwar period in the UK.

source